Back in the National Film School’s infancy, when the students themselves devised the curriculum, a method of recognising when their education was complete had to be created. 1974 was the year the first graduates began to emerge. I was part of that first wave – along with Mike Radford, Jonathan Lewis, Ben Lewin, Nick Broomfield, Steve Morrison, and others. There were twenty-two of us.

Twenty-three had started the three-year course, but Bill Forsyth returned to Glasgow at the end of the first year, disenchanted with the ad hoc nature of the teaching and the absence of equipment. Back in Scotland, he already had the wherewithal to make his films and continued to do so, completing his first and breakthrough movie, THAT SINKING FEELING, in 1979.

We spent the first year driving ourselves in the school’s long-base LandRover backwards and forwards between London (where most of us lived) and Beaconsfield Studios, acquired in 1970 as the school’s base.

Long before the sound stages were equipped for production, we gravitated between the canteen and the Anvil Recording Studio, where, under the supervision of veteran documentary director Basil Wright, we held discussions about cinema and showed our favourite films. Bill Forsyth, heavily influenced by Jean-Luc Godard’s aphorism that ‘film is truth twenty-four frames a second’, chose Andy Warhol’s 1965 EMPIRE STATE BUILDING. This one-shot silent film, which records eight hours in the life of the building, does not concede to its audience. Its sole content is the change of light as the sun moves around. We sat gobsmacked. After half an hour, the room began to empty. As far as I’m aware, Bill was left watching the film by himself.

My choice was Jean Renoir’s LA GRANDE ILLUSION, an anti-war masterpiece from 1937. Set in a WW1 prisoner-of-war camp in Germany, it’s a non-judgmental celebration of universal humanity triumphing over prejudice and national boundaries. I‘ve always thought it ironic, based on the EMPIRE STATE BUILDING experience, that Bill’s films – from THAT SINKING FEELING and GREGORY’S GIRL to LOCAL HERO – are similarly preoccupied with mankind’s foibles and the universality of human experience. Maybe Renoir’s film had worked its magic.

In his welcoming address to us students, NFTS director Colin Young announced: ‘You are the vanguard that will storm the citadel of the British Film Industry. You’re already filmmakers. Think of this place as a studio where you can develop your ideas and take the place of people who are out there earning a living.’ It was Colin’s version of ‘Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more.’

At the end of the course, we couldn’t wait to break out the grappling hooks and siege ladders and go into battle.

Except that nobody had forewarned the investors in British Film that we were coming. The big American studios, which had supported a decade of British production, including films like LAWRENCE OF ARABIA, BLOWUP, THE SERVANT, SATURDAY NIGHT AND SUNDAY MORNING, had withdrawn their finance. The industry had been left high and dry. If graduates were expecting to ply their trade, it would be in television rather than movies.

After viewing my third-year film, VICE VERSA, Colin thought I was ready to ‘go out into the world.’ He advised me to assemble my ‘graduating panel’, made up of practising professionals who would grant me the diploma that opened the door to employment. The film and television director, Jack Gold, who had generously invited me to shadow him, agreed to join the panel. As did Louis Marks, writer and BBC producer/script editor.

The diploma was a formality, and Louis took me under his wing. He recommended me to Innes Lloyd, a BBC staff producer. Innes had enjoyed a career as an actor before applying to the BBC, where he began as a producer in outside broadcast, particularly in sports. The head of drama, Sydney Newman, then recruited him to work in his department. DOCTOR WHO was his first assignment, before switching to THIRTY-MINUTE THEATRE, which allowed him to commission writers new to television. He began producing single plays and anthologies of plays around a unifying theme. His long-standing collaboration with Alan Bennett produced the TALKING HEADS series, now accepted as a high-water mark in the history of BBC drama.

Innes checked my availability for a play he had commissioned from Don Shaw. KITES was inspired by Innes’s daily constitutional on Parliament Hill Fields. There, he observed an elderly man flying a kite and, with his actor’s curiosity, wondered about the circumstances of the man’s life.

The script he sent me described the encounter between the compulsorily retired headmaster, whose prep school had failed to meet the inspectorate’s standards, and a dyslexic boy playing truant by wandering around North London parks.

Having delivered and signed off on THE HEALING – my first BBC film (described in last week’s substack) – I started pre-production on KITES.

The main location had already been chosen, and I spent several afternoons watching the kite-flying enthusiasts on Parliament Hill Fields. I took reference snaps of the best angles, so I could build a storyboard to discuss with the crew. The other locations were in West London, chosen for their proximity to BBC TV Centre in Shepherd’s Bush, the production base.

.

Casting became the next priority. In those days, the duties of the BBC casting department were limited to negotiating contracts; it offered no advice as to the suitability of actors for a particular role. So, it was left to me and Innes to choose the actors. I thought of Richard Murdoch, known as Arthur Askey’s straight man in the radio comedy MUCH BINDING IN THE MARSH. He seemed capable of playing the seedy, sardonic melancholy of the headmaster, Lawrence Hastings. Innes had another idea. An actor himself, he possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of the profession and already had Hugh Burden in mind.

Hugh Burden was a familiar face, with supporting roles in movies as various as Michael Powell’s 1942 film ONE OF OUR AIRCRAFT IS MISSING and the second Michael Caine-starring Harry Palmer film, FUNERAL IN BERLIN. I deferred to Innes’s better judgment.

I met Hugh for the first time at a costume fitting in Berman/Nathan’s Islington store. His bald pate immediately struck me. In every role I’d seen him play, and in all publicity photos (as in the picture above), he sported a luxuriant head of hair. I sensed the work of a wig-master.

I wasn’t surprised, therefore, when he appeared from the dressing room wearing the costume he’d chosen (with no reference to me or the costume designer), with the ‘Irish’ perched jauntily on his head. Again, there was no discussion. This was how he had decided he should appear. Now I realise it was his way of putting me in my place. He was my father’s age and had decided that his seniority trumped my relative inexperience.

I had a free rein to choose the boy to play Tony, the truant. I contacted Anna Scher’s Children’s Theatre in Islington. It had been running for eight years and had introduced some wonderful child actors to television. The careers of Kathy Burke, Phil Daniels, Pauline Quirke, Gary and Martin Kemp, and Patsy Palmer all began at her evening improvisation classes. Anna invited me to attend one of these sessions. It was her preferred method of auditioning. Directors would sit at the back of the hall and observe the improvisations.

One kid stood out. Steve Fletcher projected perfectly the mental turmoil of the dyslexic – the combination of artlessness, truculence and unhappiness. (Talent is abundant in the Fletcher family. His younger brother, Dexter, is now a successful movie director, having been a star performer in TV and films.)

(Steve’s headshot from later in his career.)

The script describes the collision in the lives of these two misfits. Hastings pleads, unsuccessfully, with the authorities to reconsider their decision to close his school. Frustrated, he flies his kite on Parliament Hill Fields. Tony, bunking off school, asks Hastings for a go. Initially irritated, Hastings realises it’s an opportunity to reestablish his teaching credentials: if he can teach Tony to read, maybe he’ll be allowed to reopen his school. He invites the boy to visit Heathrow airport to watch planes landing and taking off. Later, back at his digs, Hastings uses the outmoded ‘show-and-tell method’ to encourage Tony to read. When it proves ineffective, he loses his temper and accuses Tony of scuppering his chance to get his school back. The penny drops for Tony. Realising he has been exploited, he runs off. The film ends with Hastings back on Parliament Hill Fields, resigned to a purgatory of flying his kite.

In the same way as with THE HEALING, I was assigned a crew from the available staff members. Being part of the BBC system, Innes had his list of favoured cameramen. David Whitson was one of a new breed of BBC DOPs. Instead of the Arriflex 16BL, designed for ‘fat Bavarian camera operators’, as David said, he preferred to use the more modern French camera, the Eclair NPR (Noiseless Portable Reflex). Designed by camera operators for camera operators, it revolutionised documentary shooting. Fitting perfectly on the shoulder, it made handheld shooting so much more comfortable.

The production period was unhurried – fifteen days to shoot a fifty-minute drama, unlike the more hectic schedule I had to get used to on THE PROFESSIONALS and MINDER, shot in ten days.

I travelled to Ealing Studios for post-production with the editor David Martin, who went on to enjoy a distinguished freelance career, editing prestige TV shows and movies. Working with David was a privilege and a pleasure.

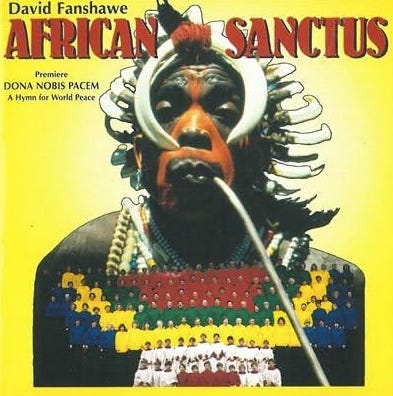

Consistent with his habit of discovering new talent – be it in writing or, in my case, directing – Innes had the idea of using David Fanshawe to compose incidental music. Fanshawe had made his name with AFRICAN SANCTUS, which integrated field recordings he’d made during his travels through Africa with the scoring of a conventional choral Mass. The combination was original and magical.

The music David composed for KITES was much simpler, and it perfectly complemented the imagery. Along with James Harpham (HAWKMOOR), Stanley Myers (HEAD OVER HEELS), and Michael Kamen (THE MANAGERESS), my collaboration with Fanshawe remains one of my most memorable.

I will always be grateful to Louis Marks for introducing me to Innes Lloyd and Innes for taking a chance on a young rookie director.

Another splendid insight into the film world, Mr Le Roi! Enjoyed it immensely. Keep em coming,