In the 1980s and 1990s, two American shows had a profound impact on British television drama. HILL STREET BLUES completely changed the police precinct format. I know that Geoff McQueen, when he wrote THE BILL, was influenced by Steve Bochco’s style, the way the police officers’ private lives spilt over into their day-to-day duties. Though Geoff had no parallel of the roll-call in which the duty sergeant advised his officers to ‘Be Careful out there’, Bob Cryer (Eric Peters) served a similar function, assigning duties and dealing with disciplinary matters. In terms of verisimilitude, it was certainly a step up from DICKSON OF DOCK GREEN.

Michael Crighton’s ER, which aired on Channel 4, revolutionised hospital drama in much the same way. EMERGENCY WARD 10 had started the ball rolling in the UK. Broadcast twice a week by ITV, it was shot in a conventional multi-camera format, similar to other soap operas. CASUALTY was the BBC’s offering, shot both on studio sets and location. First transmitted in 1986, it’s still the longest-running medical-based drama in the world. ER, however, was on a totally different scale.

During my training at the National Film School, we would-be directors made a qualitative distinction between ‘auteurs’ (those writer/directors who had a vision) and ‘mercenaries’, who would direct anything to earn their directing fee. Our prejudice followed the precepts set by the French critic André Bazin, editor and co-founder of the CAHIERS DU CINEMA, who promoted some directors over others. John Ford and Howard Hawks were favourites, thanks to their use of deep focus and long, developing shots that avoided conventional ‘coverage’ of overshoulder two-shots and close-ups, where the field of view was divided up. This aesthetic, Bazin suggested, allowed the audience to decide what was important in a scene, whereas directors from the Soviet bloc (Sergei Eisenstein, for instance) created meaning from the juxtaposition of shots, each of which had an intrinsic meaning, but implied a third from the union of the two. The classic example was the Kuleshov experiment in which audiences were shown a close-up of the actor Ivan Mosjukhin intercut with images with three different contents. The actor was praised for his versatility in expressing three entirely different emotions. Yet his face was devoid of expression. Any meaning was the consequence of these juxtapositions – meaning that was connoted, rather than denoted. The French New Wave directors, François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, started their careers as film critics, disciples of André Bazin. They applied the same aesthetic to their film criticism. And later, to their films. Both favoured developing shots and deep-focus over montage, believing that these techniques allowed the audience to participate actively in the drama they were creating.

My preferred style of shooting was greatly influenced by Godard’s A BOUT DE SOUFFLE (BREATHLESS): long, unbroken tracking shots, where the characters interacted without the interference of the editor, using improvisation to create verisimilitude and spontaneity. It was dynamic and liberating.

ER employed the same style. And was revolutionary as the first to do so on television. The fluidity of its camera movements imposed immediacy and spontaneity, and I was anxious to learn how they achieved it. I discovered it was by using Steadicam, a handheld device that allowed the operator to move smoothly from set to set and action to action, in a perpetual ballet with the actors. I was further intrigued to learn that their resident steadicam operator was Terry Nightingall, the focus-puller on HEATHER ANN, a film I produced and directed for ITV.

When Richard Broke asked me to join him on A&E, I pitched the idea of shooting in this way. But our show was shot on film, way before the advent of digital cameras. Film limited us to the duration of a four-hundred-foot roll of 16mm film, i.e. ten minutes. Even so, we found a way to coordinate action/dialogue with camera movement in a single unbroken ‘take’. It was a risky way of shooting – all or nothing. If anyone made a mistake – be it actor or technician – we had to start again from the beginning.

Apart from being nerve-wracking, the ‘developing shot’ technique has its own built-in drawbacks. It can set pitfalls for the unwary. Potentially, it can lead directors to keep the camera running for no other reason than to show off their skill. And how often is a scene’s dynamic undermined by the director allowing the camera to run, when a judicious edit would eliminate the ‘dead time’ where the camera moves for no reason intrinsic to the scene? My rule of thumb was always to fill every frame of the developing shot with ‘purpose’, with dramatic justification. ‘Deadtime’ allows audience members to become aware of the technique, which automatically distracts from the story.

A classic case of moving the camera ‘for the sake of it’ is demonstrated by Episode Three of the recently broadcast television series ADOLESCENCE, devised and co-written by Stephen Graham. I was full of admiration for the first two episodes, which ranged over multiple locations and sets, and allowed characters to walk, run, or drive from one to the other, recorded in a single shot. The shows were a tour de force – ambitious in conception and faultless in execution. In my opinion, however, Episode Three made the mistake of applying the technique to material that didn’t suit it. The episode was set in a single room and featured two characters – the teenage murder suspect and a forensic psychologist. Essentially, it was a two-handed interview scene. Nothing in the characters’ movements justified the endless patrolling of the camera around them. The technique drew attention to itself and didn’t allow the audience to become engaged in the characters’ interaction.

On a more general note, it’s a mistake to assume that these techniques represent a greater freedom from the director’s autocratic eye. Inherent in the choices a director makes is the obligation for the audience to ‘see things his way.’ In the deep-focus shot, characters are placed by the director; the focus is set by him; the space in which they appear is chosen by him. And, in the tracking shot, the camera and actors move in ways preordained by the director. Nothing is left to chance, i.e. the audience members make no choice of their own.

For producers, the developing shot is economical. It saves both time and money. The shooting ratio – as much as 9 to 1 (nine times as much footage shot as in the final cut) – is considerably reduced. Each of the five shots in fifty minutes of running time needs only to be ‘topped and tailed’ (clapper-boards and director’s instructions to cut removed). Assuming three or four takes, the shooting ratio can be more than halved. The shooting time is also reduced. At that time (2001-2), television schedules were based on achieving five minutes of edited material per day. So, a fifty-minute show would take ten days to shoot. In the case of the unbroken take, much of the day would be devoted to rehearsal. In this case, the crew and actors worked together to develop the shot, rather than the conventional method of the director blocking the action with the actors first, then bringing in the crew once the action was set. The unbroken take allowed for a much greater collaboration between actors and crew. Often, rehearsals took place in the morning and shooting in the afternoon. Three or four ‘takes’ occupied an hour of shooting time, so frequently the day’s work would be completed before four in the afternoon.

One morning, during pre-production, Richard Broke and I met with Fleur Whitlock, the production designer, at the hotel where we were staying. A television was transmitting the news in a corner. We were suddenly distracted by the images being shown. It was a live transmission from a New York feed – images of one of the Twin Towers burning. Conversation stopped as we watched, horror-struck, as another plane flew directly into the second Tower. It was in real time. For the next two hours, we were riveted to the screen, trying to understand the scale of what was happening. The air of unreality was all-pervasive. How could this be happening? Were the news feeds transmitting some ghastly disaster movie? The commentary and eyewitness reports proved it was all too real. The first tower collapsed, and a suite of images followed – people running from the cloud of toxic dust. I can’t recall how we spent the rest of the afternoon. We must have carried on working. Decisions needed to be made about the set, and we were days from beginning the shoot. All I remember is that 9-11 cast a pall over the production.

Fleur was an old friend; she’d been the art director on WHERE THE HEART IS, and we’d developed a shorthand based on each other’s foibles. One foible specific to A&E was her intolerance of paper cups. She became so irritated at having to police the set for stray cups left by careless cast and crew that she placed notices everywhere prohibiting tea and coffee cups on the set. When that proved unworkable, she commissioned metal cups inscribed with the A&E logo for the crew to use. We all had one. I failed to see the difference between a stray paper cup seen in rushes and a metal one. But we felt obliged to humour Fleur.

In the execution of the elaborate ten-minute tracking shots, I relied totally on the camera operator, Julian Barber, and his grip, Jon Head. I was asking them to operate shots designed for a steadicam, but executed on a Fisher dolly. To achieve maximum manoeuvrability, Julian pulled focus himself, thereby avoiding the extra weight of a focus puller. It was extraordinary to watch them in action, following a stretcher unloaded from an ambulance, being wheeled at high speed through the main concourse to a treatment room, where the emergency room crew took over, following their movements, from close-ups of the patient’s injuries to each member of the crew as they performed their duties.

The production demonstrated a perfect symbiosis between cast and crew, each member doing their utmost to achieve these difficult shots. When everyone gathered around the monitor to review each take, a cheer went up when the perfect take appeared. Everyone took equal responsibility.

Except for one member of the cast, whose indifference became all too obvious. On one occasion, after lunch, we gathered to rehearse for the afternoon’s work. There was no sign of him. ‘He booked a tennis court over lunch,’ one of the ADs admitted. ‘Well, get him on the phone, and tell him we won’t complete the day’s work if he’s not back soon,’ I said. We sat twiddling our thumbs until the AD returned. ‘He’s playing a five-set match, and it’s the deciding set,’ she said. ‘He’s not coming back until it’s finished.’

An hour later, he returned. I was so angry that I couldn’t speak. It wasn’t so much the potential overrun at the end of the day, but his disrespect of the rest of the cast and crew. His behaviour – fortunately rare in my experience – was unforgivable.

On THE BILL, I was faced with a similar situation. This time, I made sure that the actor concerned apologised to the crew before continuing with the afternoon’s work. It worked. He never kept the crew waiting again.

It’s depressing to discover someone who, though paid handsomely for his services, thinks so little of the job and those who help him realise it, that he makes every effort to sabotage it.

The early finishes meant that Richard Broke and I were free to explore the best eating places in Manchester, of which there are many. From working with Richard on WHERE THE HEART IS, I knew him to be something of a gourmet. We enjoyed each other’s company, having similar interests in theatre, music and art.

Early in his career, Richard had suffered a life-changing injury. A car crash in his 20s left him paralysed from the neck down. After a long period of rehabilitation at Stoke Mandeville, he learned to use a wheelchair. He regarded his disability as no more than a hindrance and refused all assistance unless he absolutely needed it. His television career, both as a script editor and producer at the BBC, was outstanding. He produced many of the BBC’s ground-breaking films, including Charles Wood’s TUMBLEDOWN, directed by Richard Eyre. It told the story of a young officer, catastrophically injured and partially paralysed during the Falklands War. As I got to know him, I wondered whether he identified with the character played by Colin Firth. Certainly, his experience as a wheelchair user would have been invaluable to the production team.

Apart from eating together, we also saw theatre shows. Richard had spent the early part of his career as Laurence Olivier’s ASM at the Chichester Festival. One of the productions was Anton Chekhov’s UNCLE VANYA, starring Olivier himself, Joan Plowright, Michael Redgrave, and Sybil Thorndike. He still had the playbill, signed by each of them. By way of contrast, we saw the Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre’s production of the same play in a new translation by Michael Frayn, starring Tom Courtney as Vanya. In the pub afterwards, Richard made some illuminating comparisons of the two productions.

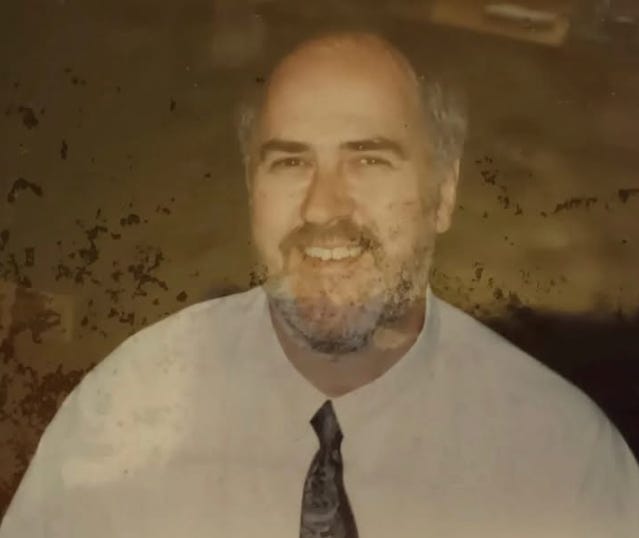

Richard was a much-loved character. When he died, at the relatively young age of 70, a memorial service was held at St Michael’s and All Angels Church in Chiswick. The church was packed. I recognised many famous faces among the mourners, actors with whom he’d worked (Colin Firth and Michael Palin), fellow producers (Simon Relph), and directors like Richard Eyre. I’m sure each of us had happy memories of a great producer and all-around great human being.

The lovely Richard Broke also exec produced Ghostwatch (1992) for the Screen One strand. though he expansively and gleefuly expounded in the documentary we made later that he had no flaming idea what we were trying to make or why the heck we wanted to make it with non-actors and real producers, witrh no music, and on video!